The making of the yield gap

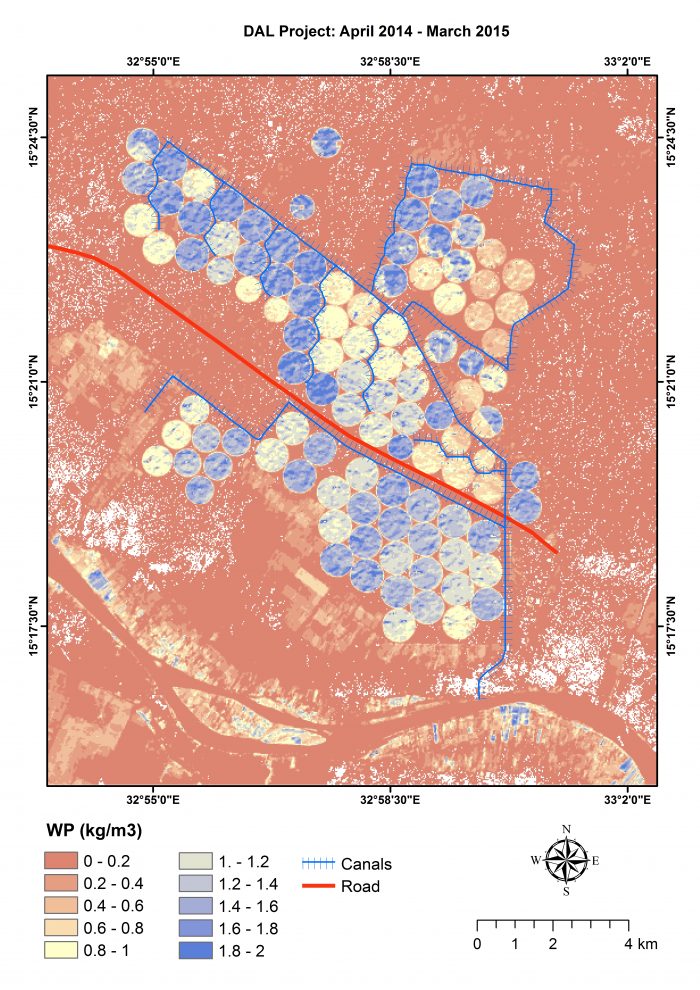

International development organisations like the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO and DWFI 2015) have high hopes in the use of remote sensing technologies to identify and close the 'yield gap'. Such a 'gap', often defined as the difference between possible yields and actual yields, is clearly visible on the map Gamal made of the Waha scheme. The circles of the high tech pivot irrigation scheme with a biomass production of 18 ton/ha are in marked contrast with the fields of smallholder cultivators South of the scheme and the lands they use for grazing.

Gamal stressed the need for transparent procedures to account for the water distribution. Well aware of the political interests in making decisions over Nile water he proposes that satellite information can be used to get a more objective picture of the consumption of water and biomass growth over the basin. “The satellite does not lie” is a phrase he uses to express this. This does not mean he thinks it is easy however. Despite the confidence in the facts produced with high flying technologies and seemingly explicit definitions of services, Water Accounting proves more than just a matter of applying the right tools in the right way. For over a year Gamal and his colleagues worked on the maps showing evapotranspiration, biomass growth and value produced in the Waha scheme. They pointed out clouds on the satellite images, the heating up of water in the Nile and extreme temperatures of Sudan as key reasons for getting the images right. Large spatial variation in climate over the basin dashed hopes of possibilities for automatic calibration of evaporation results and hopes for an easy upscaling of the methodology.

Striking in his analysis of the remote sensing images is that it features no people or other agents that might have been involved in its making. Through labelling difference in terms of the yield ‘gap’ a notions of ‘lack’ is created that resembles notions of ‘backwardness’ and ‘under’development used by colonial engineers to push for new projects to develop Nile waters. In the subsequent opposition of the high yields of Waha with the 10 times lower yields of neighbouring farms the space is created for new ‘development’ projects expressed in terms of value and yield optimisation.

With African land expressed as a grid of ecosystem services provided in US$, the continent became the ground for new resilience experiments (e.g. payments for ecosystem services, aid for trade). Rendering the landscape as values derived from the ecosystem not only positions the way forward for the ‘community’ in a very particular way, but also reconfigures spaces for the people in our convoy of cars – researchers and engineers, diplomats and entrepreneurs – as their supporters in their quest for resilience. As the market order is thus linked to sustainable development, good governance is equated with optimising yields, strengthening resource base through new technologies and support for institutions by investments and expertise of development partners. In this logic accountability/responsibility is naturalised as the “transparency of the procedures” used to visualise the yield gap. Reproducibility thus becomes the most critical parameter of legitimacy.

Yet the land, water and people Waha are not waiting in the landscape for appropriation or for new development models. As we will see, the potent lands ‘allocated’ to modern agriculture become key battlegrounds in which Amar, Yasir, Fadil and Noel redefine relations of cultivation and food consumption.