Yonas

Choke Mountains

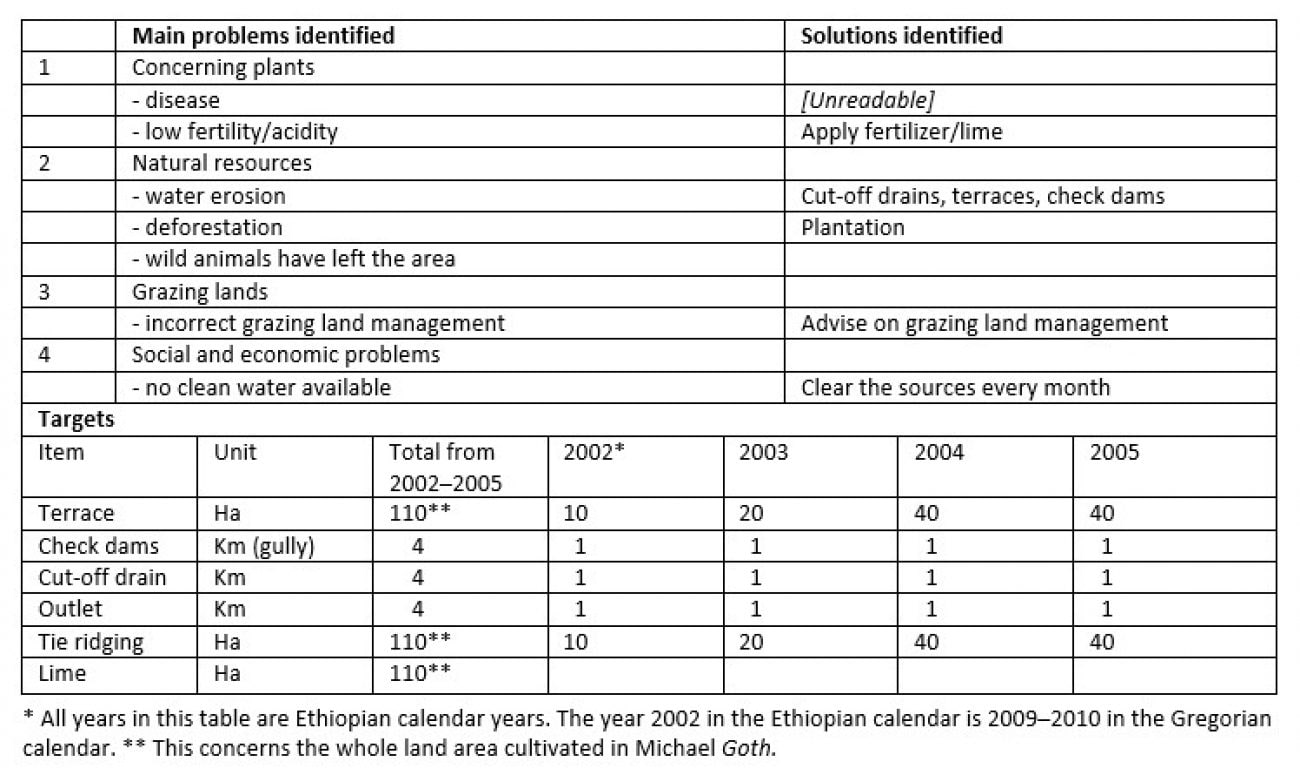

Land has been made the entry criterion for virtually all positions in the numerous development committees in Yeshat. ‘Participation’ and ‘development’ were used by the kebelle office to enrol the selected group in committees to which privileges were attached. During a 14-day meeting, for which all participants were paid 5 birr[1] per day, Yonas and his colleagues trained the council members about democracy and development and asked them to articulate the government’s previous mistakes. In the end, all were enrolled as party members. In a second meeting, the kebelle parliament elected among its members committees for women affairs, youth affairs, societal issues, economic affairs, administration, and peace. For every goth a committee for watershed development was established. Yonas is responsible for giving technical advice to Michael goth and two other goths in the kebelle. With the three committees, he develops almost identical lists of technical problems and solutions (Table 1). The committee members have little to choose as “the woreda expects complete coverage – so we have to put these figures” (Yonas). Once the plan is made, the committee does not meet again. Yonas complains that: “we [the DAs] end up nagging the farmers. We don’t have any other option really. We are like the messengers of the woreda Bureau of Agriculture and administration office.”

[1] In December 2011, 1 US Dollar equaled 17 Ethiopian Birr

In 2011 Yonas announced that development activities would become the responsibility of the newly established EPRDF political party cells (hewas) established for every goth. Its members are the people in the kebelle council. The leading role of the cell members in the implementation of the development agenda was formalized through their appointment as leaders of the ‘development army’. Cell members were assigned responsibility for the ‘performance’ of five neighbouring households through the so called ‘1 to 5 system’. Every headman reports to the cell leader, who reports to the kebelle manager on a weekly basis. To ensure that the members attend the cell meetings, Yonas organizes these twice per month on Orthodox holidays, immediately before the religiously oriented local organization – the idder – meets. Despite this, participation is usually poor, with less than half of the members participating. The cell meetings follow a fixed agenda. First, the rules are listed and the fines in case of violation thereof. Yonas stresses that the hewas – and not the idder – is the sole authority for upholding the rules. Then members are invited to report on violations of these rules and other subversive activities. Third, Yonas informs the members about development activities that month. Yet, never in the cell meetings is there mention of the most pressing issue felt by the 620 families who are not represented in the kebelle council and committees: the expanding group of people who have no land or only a garden plot – many of whom engage in sharecropping.

Although attendance at cell meetings is often poor, its leaders and those who attend engage in the performance. In return, they receive improved seeds, shovels or steel wire. More importantly, it gives them an advantage in their negotiations with the DA when the implementation of unpopular measures comes up. Government officials are also more likely to provide them support in times of disputes over land or drainage. Together, the members endorse fines for illegal encroachment on grazing land, cutting wood, and blocking drainage, thus producing a peculiar form of community-based participatory resources management. As the ‘development’ activities discussed focus exclusively on the farming domain, the council members model themselves after the image of ‘the farmer’. As their actions align with party interests, they shape party rule.

The focus on participatory soil conservation – in its equation with development – serves to keep the bureaucracy together. Who can be against sustainable development? Whereas, for some, science provides a rationale for party rule, for Yonas it offers hope for recognition of his work. Science is not a naive excuse to justify working for a party that he resents. Yonas is proud to refer to the science of the Guidelines for Community Based Participatory Watershed Management (Lakew Desta et al. 2005) in explaining how he knows the world. For him, science provides a way to legitimize his authority and a possible avenue to BSc education. The walls of his office are full of tables and graphs showing progress. Often he refers to his education at the vocational training centre to emphasize the basis of science and policy in his arguments. “If we don’t implement this plan we all go down,” Yonas explains. “We can only escape this if we conserve our soils and transform the economy. Given its good rainfall and high altitude, experts decided that this kebelle will have to focus on potatoes. Others will provide maize that will be an input for an industry that will boost the economy.”