Terrace

Choke Mountains

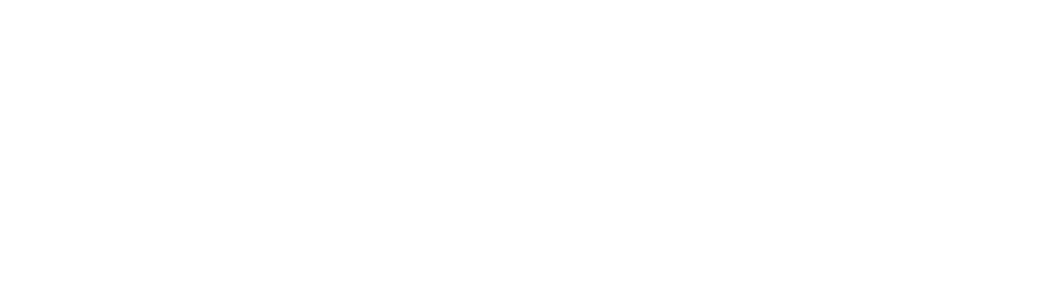

Under the SCRP programme, terraces were constructed by digging trenches and throwing the soil up the hill. Thus, local obstructions are created for water flowing down the hill. When the water flows down, the velocity drops, and silt deposits behind the bunds to form a terrace.

The soil bunds thus created trap not only soil, but also water. During heavy rain storms this can lead to sudden accumulations that create breakages in the bund. When one bund breaks, this often creates a domino effect in which water flows further concentrate, and multiple bunds are broken. If terraces have not been firmly established and precisely laid out along the contour, there are considerable risks of breakages and flooding. The SCRP project funded the construction of a medical clinic to compensate the people on the pilot sites for prohibition of grazing for three years to protect the new terraces and for frequent breakages in the two years after terrace construction. Yet as Sinan woreda does not have the resources to compensate for losses, extension agents and land users have transformed the design to prevent harmful floods. The soil is thrown downhill from the ditch instead of uphill, thereby creating graded ditches that can drain the water accumulating behind the bund. Although the implicit idea is that the bund will strengthen and benching will take place in the years that follow, terraces are constructed in such a way that benching never happens.

From the outset, it was clear that the terracing programme was far from popular. Militia are mobilized to ensure attendance at training events at least for the first few days. For example when Yohannis’ youngest son, Demaiferam, returned from a trading trip at night, they held him and instructed him to participate in training during the coming days. At the same time the trainers are frustrated by the limited effect of three decades of terracing campaigns. The woreda officer says “Now I gave a 15-day-long training course. But the farmers say ’what is new?’ They have been told this for 20 years or longer and every time they get rid of the terraces. That’s exactly the problem: there is not even one terrace (erkan, Amharic) left to serve as an example. The people in the woreda and the region think it is simple but it is not.”

During pegging, when the exact location and direction of a proposed trench is determined while taking account of the slope of the land and the spacing to neighbouring trenches, a second transformation of the terraces takes place. Yonas selected a 55 ha area on which the people of the hill would be working one particular year, knowing that most people do not want the terraces. They not only require a lot of work to construct, but also take up valuable space and make it difficult for oxen to pass during ploughing. Moreover, silt might deposit in the drainage ditches in front of the terraces, and this can lead to their overflowing and flooding the plot. The people of the hill understand that Yonas has to implement the programme because he has been instructed to do so. Several mention that “it is he who benefits from the terrace, because it gives him good salaries and a per diem.” The space between the terraces is negotiated by the DA, the terrace constructors, and the land users. Although according to the design manual the spacing has to be between 10 metres on steep lands and 21 metres on land with a slope under 8%, a compromise is reached whereby the space between the bunds differs between 14 metres on steep lands and 34 metres on flat lands (Bhrane 2012). But pegging is also the time at which the DA influences the drainage pattern to reshape relations between neighbouring farmers. By outlining terraces with ditches that cross the boundaries of neighbouring plots, near-horizontal drains are reinserted into the drainage pattern. Every ditch thus connects two or three plots to collective drains down to the river. As Yonas forcefully reinstates collaborations between neighbours who blocked drainage routes and who saw their drainage routes blocked, the terraces come to embody government-prescribed collaboration over drainage.

The digging of terraces creates further compromises in the terracing programme. The first trenches are dug in the presence of Yonas. These are – as indicated in the manual – 0.5 metres deep. As Yonas does not come the third day, both the cross-section of the terraces and the attendance instantly drop. Most terraces constructed are between 0.2 and 0.3 metres deep instead of 0.5 metres. Demaiferam and Tadesse and most other landless people leave after two days. Yohannis continues for a week and is then allowed by the cell leader to stay at home as he is old. The remaining group of landholders gathers for three weeks, but not on Saturdays and Mondays when they too go to the market and not on Sundays and important Orthodox holidays. After 15.5 days of communal terracing on 18 ha, all are instructed to terrace the lands they are cultivating. The cell leader reports every week on progress and participation. None of the kebelle officials responds to the low attendance rates however.[1] When Yonas passes the lands the following month, he instructs the land users he meets to dig their ‘terraces’ deeper. All of them promise to do so, but hardly anybody takes action. After the 40-day-long terracing campaign, only a few half terraces have been added outside the initial target area. Yonas reports that 80 ha have been constructed in Yeshat, and this contributes to the kebelle’s top ranking on the woreda’s soil conservation list that year. After that, his boss from the woreda instructs him to focus on the distribution of improved seeds.

[1] Fekadu, one of the farmer leaders, explained: “Cell leaders and kebelle cabinet farmers gave permission to their friends and relative to be absent from the terracing work. In return, the absentee farmers thresh grains and plough the land of the cell leaders. Thereafter, other farmers started to complain. They would rather pay the fines than make the terraces they do not want.”

The first heavy rainstorms of the year expose the season’s drainage pattern. In the two months after the onset of the rains, more than 50 people lodge complaints about drainage with the kebelle court and the DA. Some complain about ‘terraces’ blocked by downstream neighbours. Others complain about damage incurred by new terraces. During light rain showers, the ‘terraces’ result in more horizontal and thus safer drainage, but when the rainfall intensity is high the water accumulating behind the terraces leads to breakages (Bhrane 2012). These complaints reach the DA. Yonas observes:

“People only come to me after the soil conservation season is over and the rains have started. They come to me for everything, even things they can solve themselves. A lot is because their drains are too few or too small. I learnt that many people do not give me complete information. They present their case and hope I will comment. Then they use my words. They say: ‘The DA decided this so that is why I am doing it.’ Also, if I solve someone’s problem, I might create another one. That is why I do not want to interfere. I reject most of the complaints and tell them that if they come next year (before cultivation of the next crop) there is time to construct terraces.”

Although the yearly construction of terraces does not stop erosion in Yeshat, the state terrace construction programme reinstates the ‘farmerness’ of the Yeshat landholders and the mengist’s authority over common property resources management. A yearly cycle has thus been institutionalized in which ‘draining terraces’ appear between January and March, and slowly disappear again between June and September. The woreda government does not question its model of terrace construction. Instead, the persistent erosion is used to justify the need for development committees for soil conservation. Yet, as we saw, persistent soil erosion is not striking a hapless farming community waiting to be saved by modern soil conservation. As the terraces are made and wash away, the hill and the identities of its users take shape.