Hans

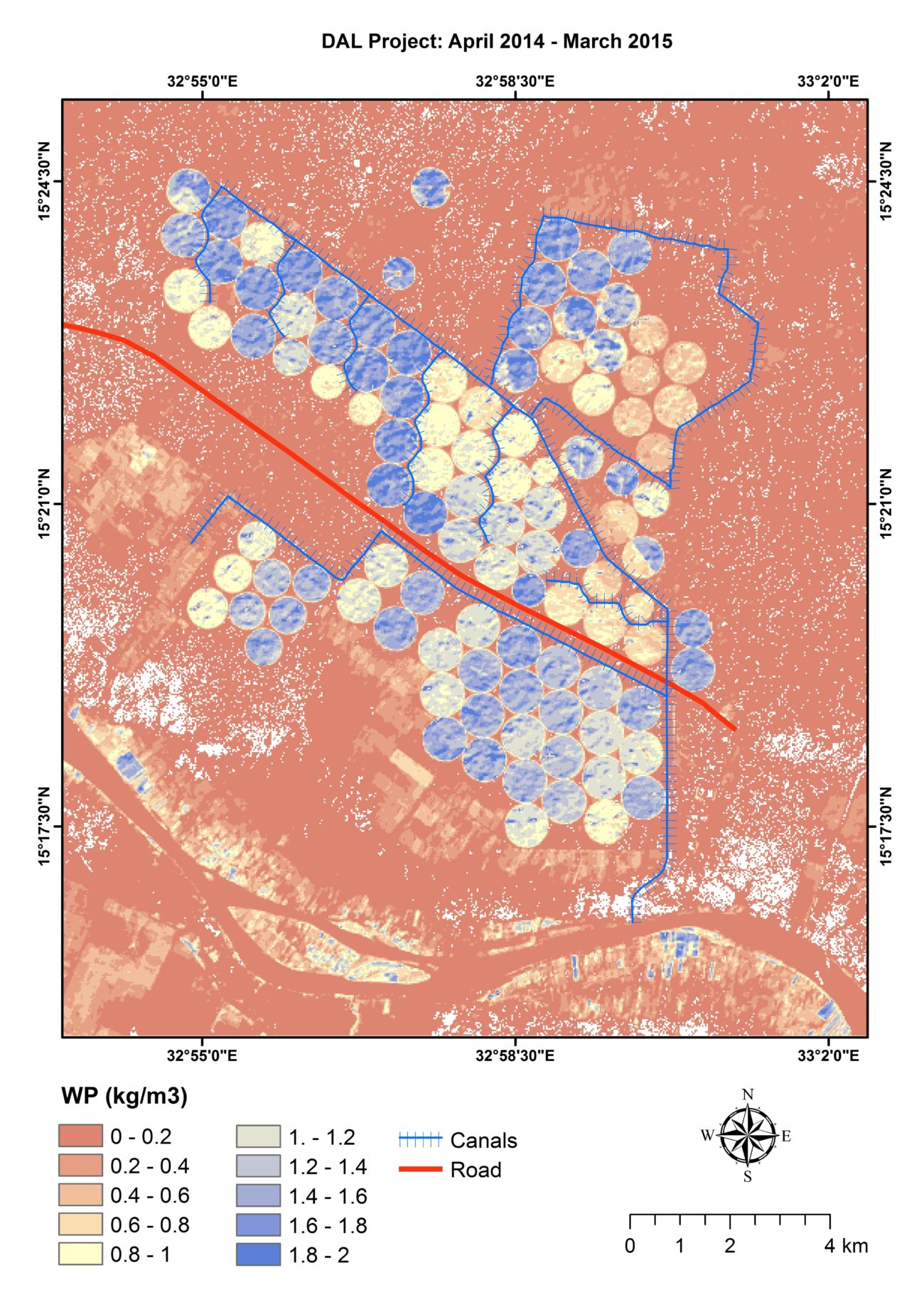

Sudan, Waha Irrigation Project

Just before entering the gate of the Waha farm our three pickup trucks meet the two cars from the Dutch embassy in Khartoum. It was the project on “Accounting for Nile Waters” which drove us together. In the first two cars were remote sensing/Water Accounting experts from FAO and a remote sensing center in Sudan and programme managers of the CGIAR who were interested in mapping the productivity of the high-tech farm. I and two other researchers in the third car were curious to find out how the contrast between green and brown landscape was being established. The embassy joined us in search of brokering opportunities to fulfil its new role in Trade for Aid.

After passing the guarded gate I was received by Fadil, the manager of the Waha farm of COM Agriculture, a branch of Sudan’s largest private venture COM Group. He hands us breakfast boxes with grapes, oranges, bread and beans.

Gamal, myself and the rest of our team had proposed to work together to better understand how knowledge of the making of the differences on the map could inform the organisation of new investments along the Nile. That high-tech agriculture in Sudan can be a profitable and productive venture in the 21st century is underpinned by the sound profits made by COM and the satellite images processed by my remote sensing colleagues. That new projects have reordered flows of land, water and food in unequal ways has been made clear by violent protests. Amongst researchers and project engineers there seems to be little constructive debate on the possibilities and dangers of new high-tech irrigation projects however. While a wave of studies on the land grab tends to focus on how engineering studies and land deals are instrumental to violent dispossession for capitalist accumulation, Sudanese and international agriculturalists and policy makers highlight the potential for more productive use of land through modern agriculture and denigrate the language of ‘land grab’ as political or unscientific. Interested in deepening this discussion, we aimed to identify the stakes and possible alliances for more just irrigation investments in the fits and misfits of alternative knowledges of the Waha scheme.

Based on conversations with and observations of scientists, policy makers, investors and water users about changing relations of land, water and food in Waha between March 2015 and September 2016 we problematize the changing conditions of river basin development at Waha as five relations/engagements through which they position themselves vis à vis others in Waha irrigation: 1. The making of the yield gap, 2. The imagining of welfare through scientific irrigated agriculture and 3. its conversion, 4. the making of the Sudanese grain market, 5. the balancing of Nile waters.