Amar

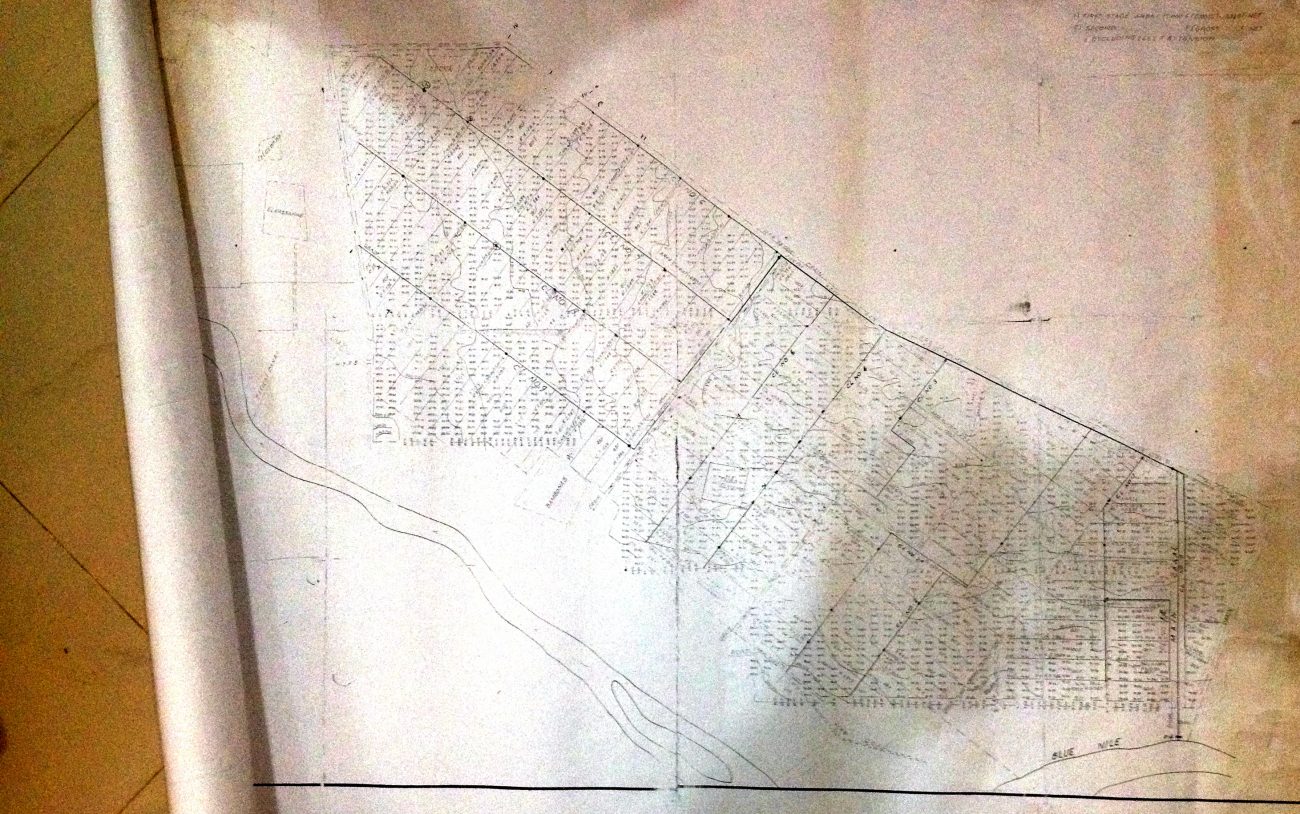

Sudan, Waha Irrigation Project

In 1990 he became a member of the Cooperative Society which invested in Waha before COM took over the Waha project. Believing strongly in the ‘science’ of large scale irrigation for cultivation by smallholders of Gezira which had become a model all over the country, he had been keen to buy a share of irrigation investment project of the Cooperative which would make the land around his home village more productive. In the first year of the project Amar bought – like 1000 other member agriculturalists, engineers, lawyers most of whom form Khartoum – two 10 acre tenancies for 1200 SDG (then 1 SDG equalled around 1 USD) each. A year later 800 tenancies were added for military officers who received a tenancy as compensation for their forced retirement by the government which was restructuring its military apparatus.

For three years the Cooperative was in business and hoped that it would expand the modest profits it made by the services it provided for the cultivation of cotton, wheat and sesame and vegetables. For Amar, like the British engineers of the Gezira, the development of the land was key in drawing people relying on backward pastoralism and recession agriculture into the modern economy.

For three years the Cooperative was in business and hoped that it would expand the modest profits it made by the services it provided for the cultivation of cotton, wheat, sesame and vegetables. For Amar, like the Gezira’s colonial planners, the development of irrigation was key in drawing people relying on backward pastoralism and recession agriculture into the modern economy. Yet the outlook for success of the Cooperative was short lived. A month after the project took off the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait. Soon after the new government of Beshir government sided with Iraq the Kuwaitis stopped investing in Sudan. As imports were severely constrained and the price of inputs went up, tenants failed to make a profitable business and repay the costs for the services they received from the cooperative for cultivation.

The government plunged into economic crisis. Eager to get rid of strongholds of bureaucratic power of previous regimes that persisted in the sizable agricultural and irrigation bureaucracies and unions, the government reoriented its attention towards oil production, real estate and communications (El-Battahani and Woodward 2013). Between 1993 and 2005 there was little government investment and less recovery of costs from Waha. The scientific model of profit sharing through in which Amar believed was reversed by the laborers who had not formal share in the agreement. With limited investments, diesel pumps and local labor they started producing sorghum and vegetables for the local market. When the Government, like Amar, saw its income curbed it revoked the land allocation to the company and the tenants and leased the land to Cemal’s company which had been taken over by his son Omer at the time and named after his father (COM).

Amar lost his tenancy without compensation. The COM enterprise bulldozed most of the cooperative scheme and constructed a new high-tech low-labour scheme on top of it. Whereas between 1990 and 2010 more than 2000 people worked on the land, COM employs only 600 people. Amar too was employed by COM through connections with two of his classmates from University of Khartoum who now work as managers for Waha. As the ‘community projects’ in Madhi for which he was made responsible did not materialize however, and relations with his home village deteriorated, he quitted after two years. Almost without exception people in Madhi and El-Hosh talk bitter about the project. Amar points at the broken tubewell constructed by COM (see picture) and complains that the new farm has brought Madhi “nothing but cancer and malaria.”

His relation with COM is not one of simple displacement however. Over the years they he, like others in Gezira, Khartoum and around Waha had become dependent on COM’s grains. Over the past 20 years COM’s became Sudan’s biggest grain importer. A large share of the bread and sorghum Amar eats is milled and traded by COM.

Yet he is optimistic about the future of Madhi: Amar proudly shows a magazine about Madhi and points at the picture of the diaspora in the Gulf who financed the new secondary school. “We built everything ourselves. Without COM and without the government” he tells us.

Amar is dreaming about a return to Madhi. Through his relations in the Ministry he has been able to register the land which his grandmother once held near Waha. He had the land leveled and connnected it to the canal through which COM supplies the land of Madhi with water. As long as he lives in Khartoum he sharecrops it to Fati, who seasonally employs Darfurian labourers to grow vegetables and fodder for the local market.