Temesgen

Choke Mountains

The division of plots into strips over the hill and the consequent drainage pattern have to be understood in the context of the land tenure system that evolved with ox-plough cultivation in Northern Ethiopia from the thirteenth century. The essence of the rist system is that people claim rights to a share of the land of their ancestors who are considered as original rightholders or the area (wanna abbat). In principle, the land was to be shared by male and female heirs. The people on the hill claim their rights as shares of a larger area held by the rist holder from whom they descended and do not attach rights to particular plots (Hoben 1973). Considerable ambiguity is created by the fact that heirs who do not inherit land after the death of a family member do retain rights to the land and can pass these on to their children. In practice, this often means that sons who were too young to cultivate and the offspring of daughters who often did not claim land at the time of inheritance claim land later.

Two elements of the rist system that persist are important for understanding land tenure and drainage of the hillslope. First, the multiple possibilities through which one can gain access to land make that the amount of land claimed by people is larger than the area of land available. Second, the ambiguity created by the multiple claims enable ‘the authorities’ to exercise power in resolving land and natural resources management disputes. As an elder stated when explaining his drainage route: “The water flows the way the king wants it.” The outcomes of disputes over land and its drainage depended crucially on the contestants’ abilities to convince the local court, which has recently been embedded in the government court system.

After the overthrow of the imperial government (1974), landlordism and the rist system were abolished and all land was proclaimed public property with the official aim to correct injustices of imperial land tenure (Desalegn Rahmato 2009). In practice this did not mean the end of the influence of the former landholding class. Mr. Eshetu, the rist holder of the hillslope, was elected as both chairman and leader of the militia (designated armed civilians who assist the kebelle administration to maintain law and order) of the Peasant Association (PA) in Yeshat kebelle.

Officials of the Dergue regime (that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991) in the woreda capital worked with Eshetu to distribute his own lands. Yeshat’s land committee divided Eshetu’s land between himself, his adopted son Mr. Temesgen, and the three tenants, Mr. Negus, Mr. Yohannis and Mr. Mersha, who had cultivated his land until then. Two women servants, Ms. Wolete and Ms. Ashene, received part of the grazing lands for cultivation.

Lands on the top part of the hill, which was partly covered by trees and partly leased out by the church for grazing, were distributed to other families. Between 1976 and 1982, the number of families on the hillslope doubled from 12 to 24. New families cleared acacia and juniper trees from steep slopes and around major drainage routes for construction and fuel. As many of these families would not increase their landholding until their parents died, they reduced fallowing of lands to intensify cultivation. This shift was enabled by the introduction of inorganic fertilizers that were heavily subsidized and provided on credit by the state.

Although, initially land distribution was welcomed by most people living on the hillslope, the Dergue government pushed through increasingly unpopular measures. The role of PA leaders significantly changed relations between people cultivating the hill. Mr. Eshetu not only involved in the distribution of land but also became responsible for the collection of the grain quota. Between February and June every family had to sell roughly a third of the harvest at a little over half the market price. Mr. Fekadu, who had one of the upstream plots draining to the gully, was put in charge of recruitment of young men for the army and for mobilization for the yearly construction of terraces. He recruited one of the sons of Mr. Yohannis, who holds land at the downstream part of the slope, to fight revolutionaries in the north.

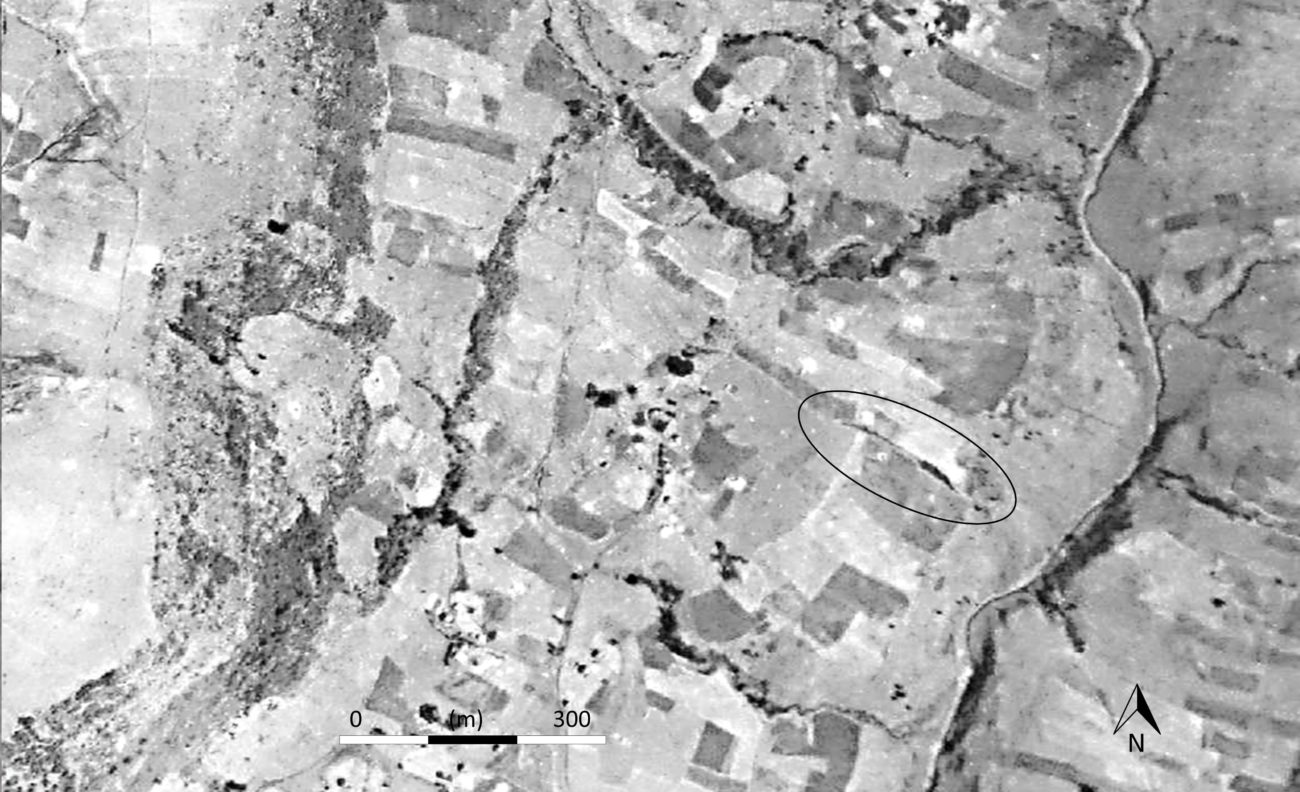

At least four rounds of land distribution between 1975 and 1985 increased the cultivated area and increased disputes over drainage. A rising number of people refused to allow their neighbours’ water to drain over their lands. By blocking the flow at the plot boundary, they refused them access to the main drains to the river. Fresh cracks appeared on new vertical drainage routes along plot boundaries. Along one of the new drainage routes thus created, a 200-metre long, man-deep, and up to 15-metre wide gully had emerged by 1982.

By the time the Dergue regime fell in 1991, fallowing had been almost abandoned. As more young families needed land, calls for land reform or new redistributions increased. The new Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF, the coalition of ruling parties that was formed after the Dergue was overthrown) kept all land under state control and included the right to arable land for all adults in the countryside in the 1995 constitution (see Desalegn Rahmato, 2009). To correct the injustices of previous land distributions by the Dergue government, a new land redistribution was implemented in 1997 (Ege 2002). Many who held official positions in the Dergue regime, like Eshetu and Fekadu, were listed as birocrat, that is, associated with the ousted regime. Consequently, their landholdings were reduced to 1 ha, whereas ‘normal’ families (amongst whom the families of their sons, like Temesgen) were allowed to keep up to 3 hectares. Most of the land freed up was allocated to young families.

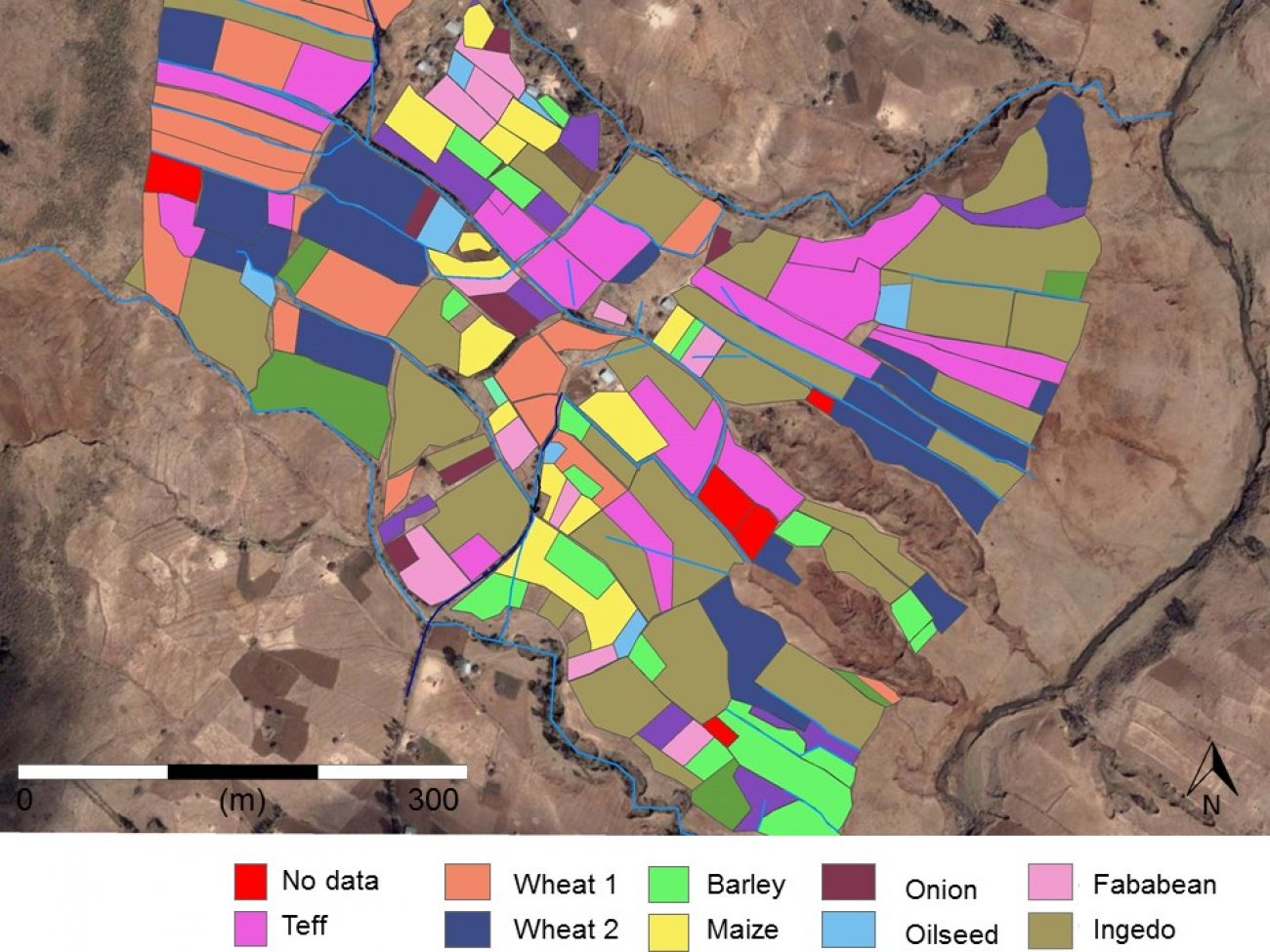

In the face of increasing competition over land amongst a growing population and aware of sensitivities of earlier redistributions, the government has refrained from distributing land to young households in Yeshat since 1997. Like elsewhere in the Ethiopian highlands (Ege 2015, Lefort 2012, Chinigò 2015) this has led to widespread landlessness amongst young households, postponed marriages, further intensification of cultivation and encroachment into grazing lands. Both the land under cultivation and cropping intensity have doubled since the 1950s, leading to a fourfold expansion of the cropped area. On the 38 ha of land around the gullies, 122 of 130 plots were cultivated during the 2010 main cropping season. This intensification has come at a price.

One cultivator on the hill explained that “while soils wash away, only stones remain”. Another stated that “these stones were grown from my land like the crops I cultivate. These big stones in my land are creating difficulty for my oxen to plough even. The stones were not here before”. The plots halfway up the slope now have more than 20% of their land surface covered with stones. Land users in Michael report that, after years of yield increases due to the introduction of new crop varieties and fertilizers, yields are now falling because “fallowing was abandoned and soils are being cultivated every year” and “the soil became addicted to fertilizer”. Others stated that: “If our lands have mouths to speak, they will tell us how much they are exhausted by ploughing all these years” and “lands are now deaf to hear our investment.” We found that average yields on the hill in 2010/2011 – reported as an average year – are low at 1.0 ton per ha for teff, 2.0 ton per ha for adja dekel, 1.0 ton per hectare for oats (ingedo), and 1.1 ton per ha for white wheat.

Farming has now become a costly business. Cultivated plots are ploughed on average five times before planting to reduce weeds and – as many in Yeshat say – to scrape fertile particles into the exhausted upper layer. Moreover, most crops no longer grow without fertilizers. Those who cannot afford fertilizers have turned to the cultivation of oats – which almost everyone in Yeshat now uses for making injera. As their oats yields are often around half the yields of people who grow the crop with fertilizers, many sharecrop out their lands in return for half the crop.

Agricultural intensification in Yeshat is paralleled with increasing social fragmentation. The involvement of some on the hill in redistribution of land and forced recruitment of others has strained cooperation between households. At the same time, the increasing scarcity of land sparks protracted struggles within households. Many young people from the hill have left the area. Yet, still half of the households in Michael goth have no access to land at all or only have a small garden plot. Some of them engage in sharecropping on the lands of old and absentee owners or landholding people who have no oxen to plough or money to cultivate. Almost all are involved in trade with the lowlands – 30 km downstream – that produce for the growing urban centres in Ethiopia.